My granddaughter Emma was born on 31st December 2019. She had been expected to meet her world on 15th February 2020, but perhaps pushed her arrival forward to coincide with the dawn of Covid-19. By the time she was six weeks old and had reached her due-by date, the corona virus was rampant in Wuhan and threatening places beyond China.

In her first twelve months Emma has witnessed a world in turmoil, brought about by the virus of the same age. It could have been better, but some places and some people seemed to go out of their way to make it worse. She noticed a stark difference between places like South Korea and Brazil, or China and the USA; the difference, she concluded, often reflected the attitudes of leaders and their policies in those places. She could also see that a focus on the pandemic (whether with good or bad results) meant that people and places were taking their eye off the ball and neglecting other, perhaps even more critical issues, such as plastics pollution and climate change.

Emma wondered why the world she had been born into was like this. It seemed obvious to her untarnished mind that if a problem was created by humankind, then surely it should also be fixed by humankind, not left to fester and grow beyond all proportion so that in the long run the problem became too big to be solved.

She looked around and saw examples of people who were able to fix things. The New Zealand Prime Minister, Jacinda Ardern, for example, appeared exemplary amongst her peers, in many ways. Firstly, she was amazingly positive on whatever issue or whichever people she connected to. Secondly, she was able to identify key challenges related to their importance on the national and global stage. And thirdly she could spell out what was required, to enable methodologies that could resolve these challenges.

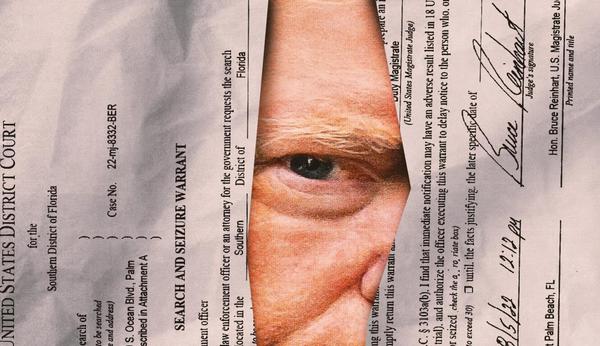

At the other end of the spectrum Emma wondered why so many leaders were content to sit back and do nothing in relation to rectifying critical global issues. In fact, it seemed that some people – leaders included – seemed hell bent on ramping up, rather scaling down, the challenges. She looked ahead to the world of 2100, when she would reach the age of 80. If she was to believe what she had witnessed in this, her very first year, she was in for a rough ride, because it promised to be a world beset with problems, exacerbated during her lifetime. From all this Emma concluded that she needed to become directly involved herself, to try to help change the direction that her world was headed in. She had come across an old Chinese proverb which said:

“If you don’t change direction, you will end up where you are going.” “Exactly,” she thought.

Emma could see there were many good people around, with brilliant ideas and potential pathways for new directions. Amongst those she noted was the historian Yuval Noah Harari, whose writings on her world – past, present and future – while at times a bit wordy (perhaps in pursuit of texts which swept all before them) were enlightened, to say the least. She tended to agree with his identification of the three mountainous obstacles that faced her (21st) Century – Nuclear War, Climate Change and Artificial Intelligence – though she knew there were a host of other, perhaps slightly more scalable summits, which also presented extremely formidable challenges, such as mass migration, species extinction, water shortage and plastics pollution.

There was also a teenager making a name for herself, who had caught the eye of people on her planet not long before Emma had joined them. She was a small young lady who seemed to possess the foresight of a worldly-wise prophet, along with the unshakeable strength of a formidable giant: the girl known to the world, simply as Greta. This fairhaired female from Sweden, a schoolgirl who had captured the imagination of so many, and had succeeded – where in comparison all before her had failed – to put one of Harari’s three major challenges for the 21st Century – Climate Change – up front and centre, on a pedestal with flashing lights, for all to contemplate and act on.

Emma enjoyed Yuval’s simple, yet at the same time dazzling way of summarizing her world, yet she identified more with the straight forward call to action that came from the Greta; after all they were sisters of the same generation. Greta’s words seemed to awaken in Emma, concerns which centred around two words, indeed two values: truth and trust. She felt that for many people in high places these two words – these values – had been sidelined, often in favour of their opposites: untruth and greed!

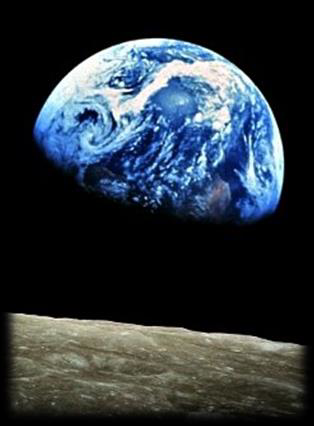

It was obvious to Emma, after sighting pictures of her blue planet, taken from space, that through good fortune she had been born into an extraordinarily unique environment.

She hung on the words of American astronaut Scott Kelly:

And yet, she was confused. People had borne witness to this spectacle from space, more than 50 years before, but they had done very little to ensure Earth’s sanctity is preserved. Emma had parachuted into a good home in Melbourne, Australia. Her parents were both truthful and trusting (as far as she could tell) and looked after her with great love and care. But she quickly learnt that her good fortune was not the experience of all her agemates on their jointly inhabited, blue planet; that in fact millions were born into hardship and suffering, which Emma struggled to imagine. Her parks and playgrounds, nutritious meals and swimming pools, were interspaced in her mind by their poverty, their refugee camps, and their debilitating wars. Yet as one, they looked to the future, from 2020.

Dwelling on the question: ‘why is this so?’, Emma surmised that these huge discrepancies, in terms of a child’s life and experience, could be attributed to a shift in the belief of humans from realities to myths. This was the most salient truth that she gained from Harari’s writing. Homo sapiens, as hunter-gatherers had placed belief in the existence of mountains and rivers, rocks and trees; but the underlying creed of society in this 21st Century had shifted, across the millennia, to an almost total faith in systems and structures cultivated over time by the minds of humans. Religion and money, nations states, political organisations and corporate bodies, all prime examples of this.

By viewing Yuval’s explanation as a theoretical construct, which provided the pillars of support to underscore Greta’s activism, then Emma began to understand the whole, and to see a glimmer of hope on the horizon. Practical actions were required that cut across humankind’s perceived realities, which were in truth, myths. This did not disavow the myths as such, but sidelined them, to enable positive and equitable actions to be delivered, in a multi-lateral and apolitical manner, without preference for religious creed, or monied conglomerates. In fact, the exalted position of money – one of Harari’s myths – should be downgraded, to enable a focus on solving the issue, rather than prioritization of cost. This brought into question – as Greta had so rightly outlined – those holy grails of market-driven economics and economic growth principles.

Climate change, Emma surmised, was just one of many challenges that her newly acquired world faced. But the same template – with minor modifications – could, in all probability, be affixed to most, if not all the others. Imagine, for example, if nuclear proliferation or artificial intelligence, plastics pollution or species extinction could be solved through multilateral and apolitical frameworks, which bore no direct allegiance to nation states or religion, AND perhaps most importantly were issue-driven, rather than money-focused. This, Emma rationalized was where she wanted to be – whether inside or outside the political sphere – she could see the most important place to inhabit was that which bridged the gap between Yuval’s theory and Greta’s practical action. She longed to be in that place, where enlightened theories became sustainable solutions.

But for now, it was time to get back to the mundane basics of learning to walk and run, read and write. How she wished she could skip over those next 20 years, to dance alongside Greta. But then, perhaps she could become the next Greta, or maybe even the next Yuval, or even better still, a theo-practical mix of the two. That, Emma decided, would be her aim: to join theory to practice and so do her darndest to help her world progress to a better future. From this moment on, that notion would consume her being and become her goal for the life that awaits!

At that very moment she was disturbed by her mum, who seemed intent on changing her nappy. Such a bore when she held all these grand thoughts on her mind

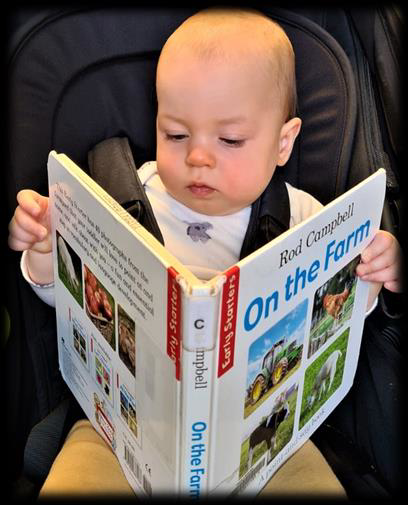

“Well, at least I’m so glad to have sorted it all out,” Emma thought to herself, as she sat in her chair doing more research. “I just need my afternoon siesta, then I can start the more detailed planning when I wake.”